It is time to explain myself — let us stand up.

What is known I strip away,

I launch all men and women forward with me into the Unknown.

Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself”

Introduction

In my time at Bryn Mawr, I have preferred (and have

been able to practice) a style of exhibition that contains the following components:

-short wall text (not more than 100 words, favoring closer to 50 words)

-an academic, impersonal voice

-thematic groups and organization of objects

-favoring including more objects than less

Therefore, for this project I embarked to curate in a style that I do not prefer as an experiment to test my beliefs of what makes a good exhibition. From the inspiration of Whitman, I have decided to engage in a process of stripping away what is known in order to understand myself. In the spirit of this course, I am working to understand my identity as a curator. This exhibition is curated from the images posted by myself and other students to social media. This process of curating served as a test for me to see if I could maintain a more subjective, colloquial voice and a longer form didactic style without a clear thematic organization of the objects. The results are hard to gauge because I am comparing one extreme (all curatorial qualities I prefer) to another (all curatorial qualities do not prefer). However, though putting it together was a difficult process in resisting my instincts, I feel that I have accomplished the goal of this exhibition: to resist my curatorial identity in order to better understand it.

“Thanks to @throckles for the expert curatorial perspective during her visit to Bryn Mawr today!”

@curatorbmc

April 17, 2017

Jodi Throckmorton’s talk reminded me of what I want curating to be: pushing the envelope of what people coming to the museum, including docents, expect to see see. I am fascinated by interrelations of the systems in a museum. It is rare that all of the programming in our exhibition is designed and performed by us, the curators. Most museums, like PAFA, have their curatorial and education departments separate. Though there were different people in charge of each of tour and program, we all held with us an agreed upon vision of the exhibition. We were there together for the all the planning stages of the exhibition and thus were privy to the same information and overall goals of the exhibition. Understanding the processes involved in making the exhibition and being able to speak on those from our firsthand experiences has made this experience quite unique.

“Great tour of Mirrors & Masks by @alexa_chabs today!!”

@curatorbmc

March 30, 2017

One of my favorite parts of this experience was designing tours and programs for our different groups. Meeting with teachers and professors to talk about the impact that our exhibition could have for their students was an incredible process. Thinking through how to utilize the objects and themes of our exhibition for someone else’s class was meaningful analytic work that helped to clarify and contextualize our exhibition into broader concepts. Looking through the plans for the exhibit and trying to make sense of what would be meaningful for another person was a collaborative process that I thoroughly enjoyed.

“Lotte Jacobi research #leggo #selfie360bmc” @mayayaby September 7, 2016

Something that I should have anticipated about this course, but didn’t, is how much it was led by my personal identity and background. As these were themes we discussed in our first semester in the planning of the catalogue, they very much influenced the objects that I selected to write about. My choices were also in part influenced by the needs of our class, particularly when we noticed that no one had selected African art objects.

“Does a self-portrait need to include a face?” @mayayaby November 21,2016

Lotte Jacobi is a Jewish woman, who was involved with leftist activists and artists around 100 years ago. My mother’s family like Jacobi are also Jews from Posen. Jewish activism has been and remains an important part of my life and this identity carries through in much of the work that I am involved in. Kathe Kollwitz, the subject of Jacobi’s portrait, lived and worked in Prenzlauer Berg. I also lived in nearly 100 years later in Berlin in that neighborhood during my semester abroad. Though increasingly gentrified, Prenzlauer Berg is still home to many artist-activists. I spent many afternoons strolling through the park there that is named after Kollwitz. My motivation to choose this photograph over the hundreds of others by Jacobi was not only because I saw them reflected in each other, but I saw them reflected through me, connecting my family’s past and my (close to) present.

“360 Last Week Throwback #4: See myself in the mirrors #selfie360bmc”

@lilililyyue

May 2, 2017

Since I was seven years old, I have trained in African dance and performance. That interest has continued through college, spending the last three years dancing with the Tri-Co student dance company Rhythm N Motion, who focus on bringing representation of dances of the African diaspora to the consortium. I also studied African drumming during my pre-teen and teen years. It felt very meaningful to focus on an African art object, especially one involved in performance. Watching videos of West African dance with Zoe Strother during her visit allowed me moments that called back to my childhood of learning dances like those in my classes. This course allowed me the opportunity to study these art objects put African performance into a new context in my life.

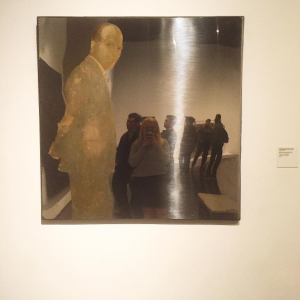

“Portrait of the Young Lady at the Museum (v) or Self Portrait Within a Self Portrait #selfieception #selfie360bmc” @mayayaby March 14, 2017

This is the last mirror selfie that I took as part of the class hashtag. This pattern started in October at the PMA on a class visit with the Intro to Museum Studies class. The painting in the background is a self-portrait by Rose Adélaïde Ducreux exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1791. This image brings together many of the themes that we discussed in class: women in art, self portraits across time (my self-portrait and Ducreux’s are more than 200 years a part) and across space (hers being from France and mine from the U.S.). Most generally, our 360 made me think about the theme of mirrors in museums and how they are displayed. Do they want or welcome the kind of selfie I made? When I posted this photo on Instagram, someone commented, “I think I did the same thing at the same place before lol love it.” People (me and at least one other person) are using this mirror for selfie-purposes, without any indication from the museum that this is invited or allowed.

In contrast to this mirror at the Met, our exhibition does encourage selfie and social media engagement. The social media component of this course has been very eye-opening for me, particularly because I did not have an Instagram before September (despite many years of urging from my friends and family). To get a sense of how to curate an Instagram, I followed museums and curators. This is something I would likely have known nothing about without this course and now I

“Last #selfie360bmc on last tour of last exhibit at Bryn Mawr on last day of undergrad classes #classof2017 #bmcbanter” @mayayaby April 26, 2017

feel that I am quite comfortable navigating this platform.

“National Portrait Gallery with BMC360 #bmcbanter #nationalportraitgallery #selfie360bmc” @alpacasandy October 21, 2016

My first visit to the National Portrait Gallery was in October with our class. I was so inspired by the exhibitions and by Kim Sajet that, with the help of Professor Levine, I reached out to her to do my thesis research there. During March I interviewed fifty visitors to exhibition, The Struggle for Justice, asking questions about how people felt they related to or did not relate to the portraits on display. It is one thing to read about portraits and how scholars have contextualized them and analyzed them. It is entirely another to speak to people who are not art historians talking about their relationships to portraits on display. Some of our readings from the first semester were confirmed by these conversations, while others were called into question. It was an enlightening experience to be simultaneously doing research about an exhibit that features portraits and then also be creating an exhibition that involved portraits. No doubt working on the two projects at the same time influenced how they developed and what the final product was.

While I am thankful for this course for many reasons, the most unexpected was this. Our trip to DC and the conversations we had there allowed me to bring together my diverse academic interests. Themes of portraiture, democracy, art, capital cities, national identity, and government, all came together in this space. I am thankful to the person who took this photo for capturing this moment of awe I had at the National Portrait Gallery. That visit and this course no doubt have shaped and continue to shape my ever-changing identity.